RPG Review: Nobi Nobi

Purple Monkey Dishwasher: The Game

Hot on the heels of my last card-based TTRPG review, another one just crossed my doorstep. Nobi Nobi (sometimes written with “TRPG” on the end) is a 2017 Japanese card-based RPG for 3-5 players, which recently completed a successful Kickstarter for an English edition by the game’s French publishers. Don’t think too hard about it. Anyway, after some delays, the cards finally have made their way into backers’ hot little hands.

“Nobi Nobi TRPG” is Japanese shorthand for “Novice Novice Tabletalk Role-Playing Game.” (“Tabletalk” is a Japanism for most role-playing-type games, since you talk at a table. Literal, ain’t it?) From the name alone, you can already see this won’t be Hero System levels of complexity.

The Collector Box contains four standalone game sets, which they call “flavors:” Sword, Magic, Thriller, and Horror.

Sword is your typical high fantasy pack, extremely medieval in tone. Fight dragons, get treasure.

Magic slots right in next to Sword and has a penchant for wizards, magic schools, and evil necromancers in high towers.

Thriller creates games somewhere between a gritty crime drama and the X-Files. The characters and prompts all have a modern-day flair, with Police Agents and Journalists and guns and computers and that kind of thing. One of the Introduction cards is Squid Game crossed with Saw. Very noir.

Horror is also modern in tone and seems tilted toward creeping terror, encroaching madness, and weird dimensional shenanigans. Maybe a zombie invasion or two in there too. Not as many pumpkins and cackling witches as you’d expect, sadly.

Each set contains:

- A rules booklet

- 8 character cards (6 for Horror and Thriller) with different characters printed on each side

- One rules reference card (double-sided, but with the same rules printed on both sides for some reason)

- One “GM” card

- One “Main Character” card

- One Opponents Table card, double-sided

- One Objects Table card, double-sided

- 8 Introduction cards (6 for Horror and Thriller)

- 8 Epilogue cards

- 40 Scene cards (32 for Horror and Thriller)

- 20 Light cards (16 for Horror and Thriller)

- 20 Darkness cards (16 for Horror and Thriller)

- 6 six-sided dice (three light, three dark), colored with each box’s theme

There aren’t any extra gewgaws in this game; no tokens or maps or meeples. You’re also not beholden to use just one genre per game. If you want to add magic to your sword game, for instance, just shuffle each set’s Light, Darkness, Introduction, Scene, and Epilogue decks together, let players choose from either box’s character cards, and then draw from the combined decks during the game. The downside is having to separate the decks out again afterward, which is really only a problem if you’re anal about keeping things organized (like me. eye twitch).

Setup is as simple as “players pick a character card, shuffle all the decks, and put them in the middle of the table.” Bang zoom, we’re playing.

Okay, But What Are We Playing?

Frittered away by detail

Here’s the entire game cycle of Nobi Nobi. Ready?

- Choose one player to be the first GM. Give them the “GM” card.

- The person to their left is the Main Character of this scene. Give them the “Main Character” card.

- The GM draws an Introduction card and reads it aloud. This sets up the whole general vibe of the adventure. Everyone lets that sink in for a second.

- The GM draws a Scene card and reads it aloud. It’s either a Skill Check card that can be resolved by a die roll, or a Role-play Challenge card that has to be talked out to the GM’s satisfaction.

- If the Main Character succeeds at either the roll or the role, they draw a Light card and add it to their hand. If they fail, they draw a Darkness card instead.

- The former Main Character becomes the GM and the player to their left becomes the Main Character.

- GOTO 4

- After three times around the table, the GM draws an Epilogue card and reads it aloud. The group combines their powers and accumulated cards and hopefully succeeds in the final challenge.

- The players all go home satisfied (?).

It’s a slow game of Nobi Nobi that takes more than an hour from start to finish.

While it’s simple enough even a caveman can play it, I’m ambivalent about the “GM/Main Character always passes to the left” rule. Some folks are just better than others at certain roles, and it would suck to have a dud counterpart through the whole game. Personally, I’d suggest that any group of 4 or more players should pass the Main Character card one extra chair down every time they complete a round, to ensure that everyone gets a unique pairing every turn.

Nobi Nobi uses a simple 2d6 + Stat vs. Difficulty Number system to resolve Skill Checks. Different characters have special abilities which can alter this (see below).

All the Cards

Relax, guy, be vague

Character cards are larger than the other cards, mostly to accommodate the cutely sketchy character art by game designer and “Love, Death & Robots” mangaka Takashi Konno. At least they have their priorities straight. Each character has two stats, Power and Technique. There’s no real balancing going on; some characters are obviously more powerful than others in raw stats.

However, this imbalance is countered by each character’s Ability, a rule-changer that applies only to them. For instance, the Paladin gains +3 to any roll when facing an opponent in noble combat, while the Assassin automatically succeeds in any check, no matter how high, if they roll a 1 on either die. A few are goofy (but fun); the Samurai can drop five dice on their character card from a height of at least 10cm, and if any die comes to rest on the character portrait’s sword, they automatically succeed. Otherwise they fail.

According to the rulebook, Abilities are categorized as Solo, Assist, and Permanent. A Solo Ability can only be used while that character is the Main Character. Assist Abilities can be offered to the MC when it’s not your turn. Permanent Abilities are just blanket always-dos, like the Paladin’s +3 above.

Note that I said “according to the rulebook.” The cards as printed also show two other Ability types, “Self” (which is obviously “Solo” and the proofreader goofed) and “All.” “All” is undefined in the Ability section, though elsewhere the rules state that only “Permanent” and “All” Abilities can be used during the Epilogue. So it’s a deliberate type.

The most logical assumption is that “All” Abilities are switchable from “Solo” to “Assist” where applicable. But they really should have said something.

Introduction cards are all broad-strokes adventure starters. The floor collapses beneath your feet, plunging the party into the deep dungeon. A mysterious benefactor approaches the party and offers great riches for a “simple” task. A terrible army appears on the horizon and only your group can stop it. You awaken in a twisty-turny set of passages, all alike. Everything else that happens in the game supposedly hangs from this skeleton.

Introduction cards are open-ended enough that they funnel the game in a certain direction without saying “and this is exactly what’s going on.” This gives the GM an opportunity to fill in the details with …

Scene cards are most of the meat of the game. Every time the GM mantle passes to a new player, they draw a Scene card, read it aloud, and try to work it into the story so far.

Making an entertaining game session out of these cards super duper really depends on the players’ narrative chops. That’s true of any RPG, of course, but it’s especially true here. Scene cards run the gamut from “you have to stop the evil ritual” to “You are all in prison” to “you are now in a baking contest.” Often they’ll drop the group into a fracas in medias res. What bridges the ongoing story to this new predicament? The GM’s imagination and nothing else.

In a four-person, three-round game, players will deploy twelve random Scene cards. Coherence is almost always out the window before the end of round one as the game becomes an extended improv routine. If the players are good at that, and everyone’s dialed in, and the cards are kind to you, this has the potential — the potential, mind you — to be really wild or really funny or both. If not all the above is true, everyone will instead sit around sighing, “Okay what monkey cheese bullshit happens to us THIS time?”

The rulebook has this to say about Scene cards:

“Sometimes, the Scene card that has just been drawn will seem to have very little to do with the previous one. The GM’s task is to weave the scenes together into a story. It doesn’t matter if the connection seems far-fetched or forced; the most important is to make it creative. Don’t worry about the result; strange and unexpected connections sometimes make the most interesting stories!”

In my Pocket Odyssey review, I was disappointed by how little guidance GMs got. So it’s pretty impressive to find a game that has even less. Bear in mind that everyone at the table becomes the GM, so everyone has the “honor” of wracking their brains trying to slap another hunk of random action onto the teetering plotline. This is neither a game for shy people nor story sticklers. Only the loosiest of goosies will prosper.

Light and Darkness cards are what the Main Character draws at the end of their scene; Light if they succeed, Darkness if they fail. In a way, both types of card are level-ups, giving bonuses to stats (some quite hefty) or new Abilities.

The main addition these cards bring are character beats. Light cards are full of bright positive things that the character either gains or reveals, like a vow of non-violence, a fancy new vehicle, or a famous family name that you must uphold. Darkness cards give your characters troubles like a gruesome reputation, awareness of a sinister plot (which may or may not be real), or a hopeless devotion to one of the other PCs. How these beats change your character are up to you and the GM du jour.

Despite their names, both card types offer palpable mechanical improvements to a character, and never take anything away. “So what,” you may ask, “are the downsides to failing?” To which the answer is pretty much “Eff all.” I mean sure you’ll slowly reveal a dark past that makes you a grim antihero instead of a shining paragon, but that might be your kink. The game doesn’t judge.

In truth, a couple of Abilities do synergize with these cards. The Necromancer from the Magic box gains power by having Darkness cards, for example. But the vast majority of the time it’s all just window dressing that the players and GMs have to make significant on their own.

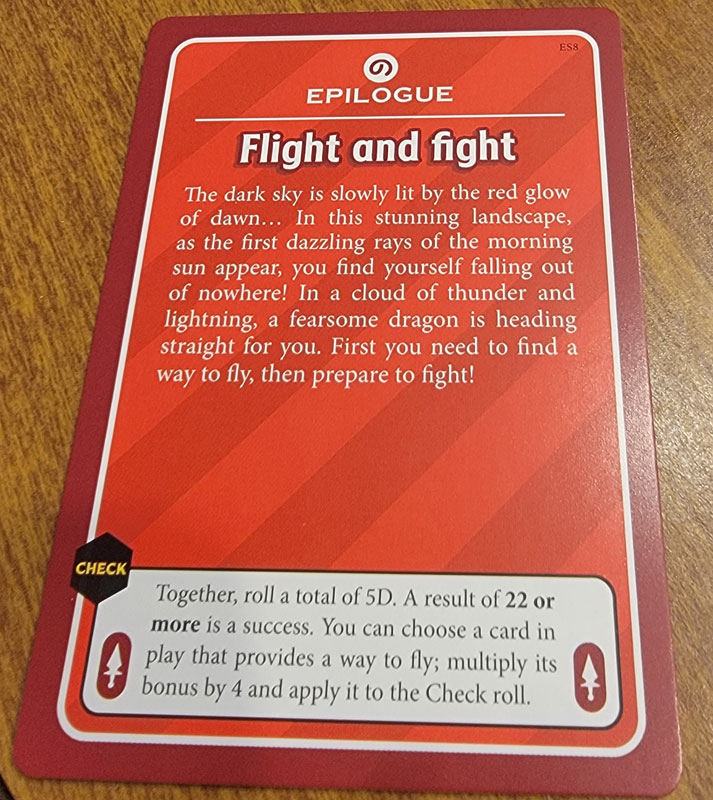

Epilogue cards are drawn after the GM role has made three circuits of the table. They’re essentially Scene cards that involve the whole group. They nearly always drop the party into a huge predicament, and either everybody has to pass an individual check or the party has to somehow combine their powers to beat an enormously high check score.

The chance that an Epilogue card in any way resolves the story of a typical Nobi Nobi game is so close to zero as to be negligible. There’s no thematic throughput from the Introduction to the Epilogue. It’s always just “Suddenly, CLIMAX!”

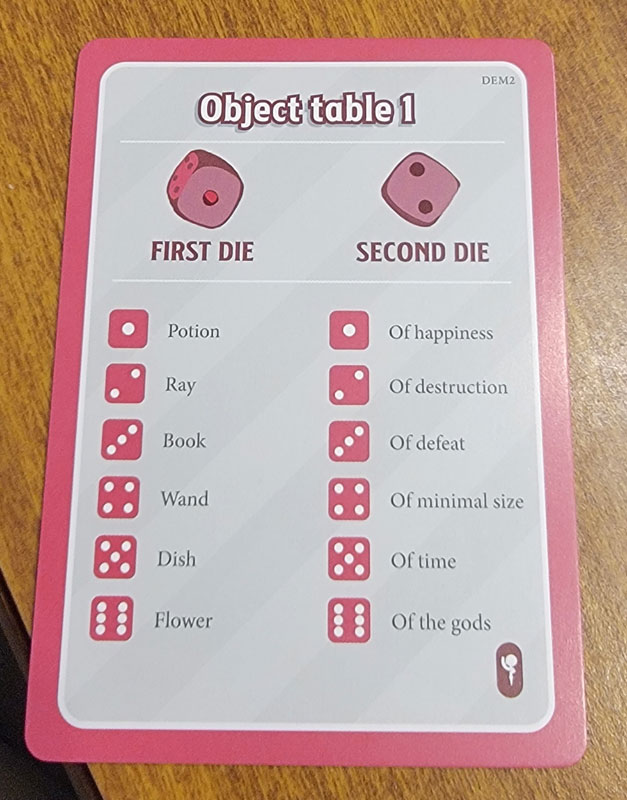

Opponents Table and Objects Table cards are just there in case the GM needs to create a random NPC, monster, or MacGuffin and can’t think of anything off the top of their head. Roll 2d6 on a list and prepare to be inspired.

Each box set has different cards, so if e.g. you need a potion, crack open the Magic box.

GM and Main Character cards have “GM” and “Main Character” printed on them. Whee.

The Presentation

Are you watching closely?

The Collector Box slipcover is made of a laminated sturdy cardboard with a magnetic flap strong enough that it can be bounced around without worrying about it opening.

Each individual game box’s quality is on the high end of standard. The thick laminated boxes are taller than the decks of cards they contain, but not quite tall enough to hold two full decks shuffled together. The boxes each have an off-center divider which holds half the cards snugly to one side, with enough room to hold the rest of the cards plus the dice on the other. That snugness makes it difficult to remove the cards without flipping the box over.

The character cards are largish placards about 3 1/2” x 5”, while the playing cards are standard playing card size. Y’know, like you do. The finish is satin and adequately “grippy,” so the cards won’t slide around much.

The rulebook is a full-color, 20-page, saddle-stitched pamphlet which just barely fits the box. Each set’s rulebook contains identical rules laid out identically, but the illustrations are all customized to fit the box’s theme, and they’re each printed in the color scheme of their box set. It’s nicely well-presented.

There’s one unfortunate peccadillo. The font size on the cards and rulebooks is pretty small, and the text is sometimes printed over mid-range background colors in a way which is probably not ADA compliant. This makes the cards and rules hard to read sometimes, especially if the lighting isn’t perfect in your gaming area. People with visual impairments should be aware of this before picking it up.

Conclusion

The sooner we’re rid of it, the sooner to rest

Nobi Nobi is a silly game. Full stop. It’s constantly at the mercy of the winds of chance. Good players can spin it into gold, but more mediocre players might butt their heads against its incessant randomness.

Games have no danger. All characters are guaranteed to live through to the end. Someone who fails at everything will be able to stay even with (or even get ahead of) the guy who skates through every challenge. That would make this a good game to play with kids or novices (“nobi nobi,” to coin a phrase), but the kind of people who passionately argue for hours about “game balance” will pop a clog.

I honestly don’t know whether I can blanket-recommend this game. It depends on who you play with and what everyone at the table is looking for. Personally I’ve had fun in the couple games I’ve played, but I’m a fundamentally silly person. I’ve also seen players report great frustration with it. That’s life, I guess.

“It’s good for what it is, if that’s what you want” is the best I can do. One thumb, mostly up.